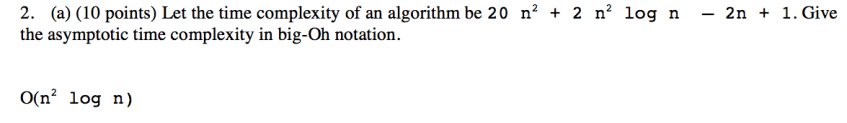

The answer is Big-O(n^2 log n) Could someone show me the steps necessary to go from regular time complexity to asymptotic time complexity?

The answer is Big-O(n^2 log n) Could someone show me the steps necessary to go from regular time complexity to asymptotic time complexity?

Asked By : Connor Black

Answered By : Realz Slaw

- You can throw away the constant coefficients of each term.

- The fastest growing term is the only one that matters, since as $n rightarrow infty$ (approaches infinity), the other terms will be insignificant.

So due to rule 1, $20n^2 + 2n^2log n – 2n + 1$ becomes $n^2+n^2log n – n + 1$. Now, only the largest-growing term here will be significant. The other terms will be insignificant when $n rightarrow infty$. The two first terms are obviously much faster growing, since they have an exponent of $2$. The second term is faster than the first because it has a non-constant multiplier that is more than $1$ as $n$ approaches infinity; it will thus make the term grow faster. Thus the second term becomes the only one remaining. Now for the math:

How do we know we can throw away constants?

Because, let $f(x)$ be that term, then $af(x) in mathcal{O}left(f(x)right)$, where $a$ is a constant, not dependent on $x$. What this means, is that $f(x)$ will grow at the same rate as $af(x)$, (as $x rightarrow infty$), even if it will always be larger by a multiplicative constant. How can we prove this? The definition of $f(x) in g(x)$: $$|f(x)| le ; M |g(x)|text{ for all }x>x_0.$$ Where $M$ is some positive constant, and there exists some $M$ and $x_0$ that makes this true. So let’s set $g(x)=f(x)$: So the question becomes: Does there exist an $M > 0$ and $x_0$ such that this holds true? $$|af(x)| le ; M |f(x)|text{ for all }x>x_0.$$ The answer is simple: set $M=|a|$, then we get $|af(x)| le ; |af(x)|text{ for all }x>x_0$, which is of course true, since they are actually equal. And since this is true, we get $af(x) in mathcal{O}left(f(x)right)$ as per the formal definition of big O notation.

How do we know we only care about the fastest growing term in a polynomial?

See wikipedia section on properties of big O notation:

If a function f(n) can be written as a finite sum of other functions, then the fastest growing one determines the order of f(n). For example $f(n) = 9 log n + 5 (log n)^3 + 3n^2 + 2n^3 = O(n^3) ,, qquadtext{as } ntoinfty ,!.$ In particular, if a function may be bounded by a polynomial in n, then as n tends to infinity, one may disregard lower-order terms of the polynomial.

To prove this, we need to prove that given two terms in a polynomial, if one grows as fast or faster than another, then the entire polynomial is as fast as the faster growing term. Formally: $left.f(x) + g(x) in mathcal{O}left(f(x)right) vphantom{Bigg|} right| _{g(x)in mathcal{O}left(f(x)right)}$ Translation: term $f(x)$ plus term $g(x)$ is as fast as $f(x)$ if $g(x)$ is bounded by $f(x)$ (bounded means: grows at most as fast as). Proof of this statement: $$ begin{eqnarray} &&&hspace{2pt}&hphantom{(1)}&hspace{1pt}& exists_{x_0,M>0} ~ left|f(x) + g(x)right| &stackrel{?}{le}& Mleft|f(x)right| ~~~x>x_0 text{ as } xrightarrow infty &&(1)&&text{Reformulate question} g(x) &in& mathcal{O}left(f(x)right) &&(2)&&text{Given} exists_{x_{g0},M_g>0}~left|g(x)right|&le&M_gleft|f(x)right| &&(3)&&text{Restatement of (2)} &&~~~x>x_{g0} text{ as } xrightarrow infty f(x) &in& mathcal{O}left(f(x)right) &&(4)&&text{Reflexive} exists_{x_{f0}=0,M_f=1}~left|f(x)right|&le&M_fleft|f(x)right| &&(5)&&genfrac {}{}{0}{}{text{Restatement of (4) via}}{text{def., choosing values}} &&~~~x>x_{f0} text{ as } xrightarrow infty exists_{ genfrac{}{}{0}{} {x_{f0},x_{g0}} {M_f=1,M_g>0} } ~|f(x)|+|g(x)|&le& M_fleft|f(x)right|+M_gleft|f(x)right| &&(6)&&text{Adding (3), (5)} && ~~~x>maxleft(x_{f0},x_{g0}right) text{ as } xrightarrow infty &le& left(M_f+M_gright)left|f(x)right| &&(7)&&text{Simplying (6)} &&~~~x>maxleft(x_{f0},x_{g0}right) text{ as } xrightarrow infty |f(x)+g(x)| &le&|f(x)| + |g(x)| &&(7.1)&&text{Math} exists_{ genfrac{}{}{0}{} {x_{0}=maxleft(x_{g0},x_{f0}right)} {M=M_f+M_g} }~left|f(x)+g(x)right|&le& Mleft|f(x)right| ~~~x>x_0text{ as } xrightarrow infty &&(8)&&text{Simplifying (7,7.1)} M_f &=& 1 &&(9)&&text{Valid/chosen in (5)} x_{f0} &=& 0 &&(10)&&text{Valid/chosen in (5)} exists_{ genfrac{}{}{0}{} {x_{0}=maxleft(x_{g0},0right)} {M=1+M_g} }~left|f(x)+g(x)right|&le& Mleft|f(x)right| ~~~x>x_0text{ as } xrightarrow infty &&(11)&&text{Simplifying (8,9,10)} end{eqnarray} $$ Thus we can construct a valid $M$ and $x_0$ given a valid $M_g$, and $x_{g0}$, which we know exist, because $g(x)in mathcal{O}left(f(x)right)$ is given.

Best Answer from StackOverflow

Question Source : http://cs.stackexchange.com/questions/14845 3.2K people like this